- Home

- Miles Swarthout

The Last Shootist Page 5

The Last Shootist Read online

Page 5

“Ma, I ain’t wheelin’ any lungers around. You want me to catch somethin’ bad, get sick, too?” Gillom threw his linen napkin down on their long dinner table, vacant now except for the two of them, his beefsteak half-eaten. “I’ll find a job, eventually. Maybe work in a gun shop, for a gunsmith. Learn that trade.”

“Guns.” Bond Rogers blew frustrated air through her lips, like a tired horse.

“Just give me some time to get my life straightened out after all this trouble.”

“You seek trouble like a moth does the flame.”

With a backhanded dismissal, Gillom headed back to his room. There, by the light of a coal oil lamp in the sanctuary of his clothes closet, behind the curtains, he cleaned Books’s revolvers. With a wooden pencil he poked an oiled rag down the Remingtons’ barrels to clean out old powder from an afternoon of tree blasting. He oiled the cylinders and replaced the .44-.40 cartridges and spun them shut. He didn’t leave one empty as a safety under the hammer, for he knew, barring a miracle, he’d be using these guns tonight. Hope to God I don’t need all twelve cartridges. What was it Books said about shoot-outs?

“It isn’t being fast, it’s whether or not you’re willing. The difference is, when it comes down to it, most men are not willing. I found that out early. They will blink an eye, or take a breath before they pull the trigger. I won’t.”

That’s how he’d done it all those years, Gillom thought. Survived. Gunmen of all stripes, fast and slow, young and old, white or whatever race, trying to shoot him, blast him dead. But his steel nerves, quick reflexes, and steady aim always saved his ass. J. B. Books—the shootist. Well, a cool countenance and a calm hand will save mine, too.

Gillom got to his knees. Just in case, he put more cartridges into both pockets of his wool coat, for quick reloading. He buried the double holster under some dirty clothing on the wooden floor and was backing from the closet when his mother walked into the bedroom.

“What are you doing in there?”

Startled, Gillom turned, then deliberately calmed his emotions, practicing control.

“Cleaning my boots.” He graced his mother with his most conciliatory expression. “Ma, I’m sorry for our arguments. We’ve both been greatly aggravated by all this … bloodshed. Mister Books shook this house up but good. But he’s gone now, I doubt to a better place, so we can try a fresh start. I’ll look for a good job tomorrow. And find one. I promise.”

Her smile finally bloomed. “Oh, Gillom. You can do it, I know you can, dear. Learn some decent, respectable profession. And finish your high schooling. Go back to Central School next year, after this awful business dies down.”

Now Gillom smiled. “Maybe.” He was careful in the hug he gave her, so she didn’t feel any cartridges rolling around in his coat pockets.

Gillom heard his mother lightly snoring upstairs through his thin ceiling, so he had no trouble slipping out his bedroom window later that night. He chanced wearing his double rig under his wool coat. It was Sunday and long after dark, when even the six hundred gamblers in the forty licensed gambling halls and the hundreds of whores in the bagnios and cribs and dance halls lining Utah Street all the way down to the Rio Grande had to catch their breaths after another weekend’s lucrative work. The local saying was, “When anybody has a dollar in his pocket, he heads hell-bent to El Paso to get rid of it.”

Gillom had been to San Jacinto Plaza many times with his mother. Peering through the darkness as he walked up to it, he noted the two highest structures in the block-long plaza—the bandstand and the fountain in the middle, constructed of rocks and mortar from which a large plume of water shot up in the air during the daytime, when it was turned on. A stone catch basin around it was filled with water five feet deep. Grass grew around this fountain in a ring between the water pool and a chain-link metal fence anchored by iron poles that encircled the whole layout, at least thirty yards wide.

The metal fence had been constructed to keep little boys out and the alligators in. Local kids had a penchant for poking the alligators with sticks and throwing stones at them while they dozed in the grass beside their waterhole, seeing if they could be provoked. According to local legend, six baby alligators had been shipped by train from the swamps of Louisiana by a friend of one A. Muhsenberger, a mining man, as a joke. Having no way to care for them, Mr. Muhsenberger had prevailed upon the city council to add the gators to the plaza menagerie. A few had survived attacks by eagles, owls, coyotes, and little boys to thrive on a diet of horse and cow carcasses, stray dogs, and the occasional child. Several of these pet gators had grown to be a good ten to twelve feet long.

The most famous incident happened after a convention of dentists, drinking too late in an El Paso saloon, got into a loud argument over how many teeth an alligator actually had? A number of these dentists, armed with more booze and torches and ropes, set off into the dark midnight to actually find out, but were stopped by deputies before they could conduct any alligator dental examinations.

Gillom had no interest in arousing the ancient beasts as he walked delicately across the long plank bridging the stone basin to several rock steps leading up to the top of the rock fountain in the middle of the gators’ pond. Looking down into the murky water, he could see several pairs of orbs as red as fireholes glowing in the cairn beneath the fountain he was about to climb. Stone masons had thoughtfully hollowed out an underwater grotto underneath the fountain where the gators could rest in peace out of the hot sunshine and away from rock-throwing kids.

The raised fountain gave the crouching gunman good vantage of the whole plaza in every direction, and by moving around its uneven, eight-foot-high stone sides, he could have cover. Still, it was unnerving, perched atop rough rocks in the dark, watching an occasional ripple cross the pond to lap upon the gravel rim at the edge, or to hear an exhalation from the grotto beneath, a shivery breath from a prehistory entirely foreign to this high school dropout. Gillom Rogers was very aware of what lurked below.

He didn’t have long to wait. Serrano’s vengeful relatives showed up half an hour early, similarly thinking to gain an advantage. The cousins rode slowly north up El Paso Street from the Juarez bridge, dismounted to loose-tie their horses to another chain-link fence that had been erected around the whole park to keep horses and rabbits from grazing its flowers and grass under its pepper trees down to nubs. The young Mexicans didn’t pause, hopping the waist-high fence, then pulling their old pistols to move out along either side of the plaza, heading toward the raised bandstand.

Gillom slid down the far side of the fountain from them. He’d left his new Stetson at home, to present less of a profile against the lamplight from the windows of the luxurious new five-story Sheldon Hotel fronting the north side of the plaza. Several saloons along the south side of San Jacinto Plaza were still open, but other stores and commercial buildings around the park were closed this late Sunday night and the plaza deserted. He hugged the rocks of the fountain’s construction and slid over the top to the opposite side again as the two Mexicans passed him on either side, looking cautiously about everywhere but up at the fountain itself, for no one would dare venturing into that alligator pond after dark.

The vaqueros wore dark clothing, one had a sombrero, and when they reached the covered bandstand only ten yards north of the pond, the taller man dashed up its five wooden stairs to get better vantage. Serrano’s closer relative waited below, bouncing nervously on the toes of his boots, steeling himself for a bloodletting. Gillom could hear their Spanish whispers. Might as well start the ball, he figured. Didn’t come here to hide from a fight. He chewed his lip as he rose to stand atop the flattened top of the rock tower, where the brass nozzles of this big fountain’s three pipes blew towering spray from these rocks in the daytime.

“Buscaderos! This is your chance! Take your best Sunday shot!”

“Cuidado, Cesar!” yelled the man leaning on the bandstand’s low railing. His jumpy relative below was already jerking his pistola up and firing

a wild shot at the shadowy figure standing atop the rock tower.

Gillom knew it was gospel among gunfighters that the man who survived a shoot-out took his time. So he took his precious time, too. As a second, errant bullet flew past, he sighted down his stretched arm and with one shot, plugged the kid right in his breadbasket. The young vaquero staggered at the slug’s impact and fell on his seater, the shock of a stomach wound paralyzing him. The older Mexican clattered down the bandstand’s stairs to his cousin’s aid, who sat slumped forward like a rag doll with the stuffing knocked out of him.

“Cesar! Cesar!”

His cousin couldn’t answer, gurgling blood instead. This enraged the aggressive youth who had instigated this vendetta, and he jumped to his feet.

“Pendejo! You kill him!” Firing his own pistol, Gold Tooth winged a bullet off the rock under Gillom’s boot. Jumping at the ricochet, Gillom pulled his second revolver and cocked and fired both .44’s from his hips at once! One of his lead slugs caught the second Mexican, spinning him around and down on the dirt walkway next to the bandstand. Gillom couldn’t take any further chances. Straightening from his crouch, he extended his right arm, thumbed the hammer, and aiming down the unsighted barrel of his Remington, went cat-eyed in the dark.

“Buenas noches, hombre!” His careful shot from twenty-five yards, aiming downward, found its target again, hitting the second troublemaker in the chest and knocking him flat. Gillom didn’t stop to admire his shooting, but quickly reholstered and clambered down the rock tower’s side. He heard a band in a distant saloon essaying a standard, “Where the Lilies Bloom,” as he tiptoed rapidly across the plank board bridging the pond.

With one gun drawn again, Gillom kicked the older, more dangerous man to ascertain if he was dead. Not worried about his relative still slumped, breathing raggedly nearby, Gillom quickly unbuckled Gold Tooth’s holster and took his pistol, then rifled the young man’s pockets finding some dobie dollars and a pocketknife. Don’t leave anything identifying him behind, he remembered.

He was pulling the dead man up when he heard a loud hiissss behind him. The alligators! Christ, they hunt at night! His mind raced. And eat dead meat! Gillom turned to see two bright pairs of eyes staring unblinkingly at him from dark water. One of the beasts had its elongated flat snout resting on the pond’s concrete lip, several of its eighty long teeth glistening in the moonlight.

Gillom heaved, waltzed the dead Mexican around, closer to the chain-link fence, then with a big hoist and a shove, pushed his stalker over the low, iron-poled fence backward into the pond with a splash. Gold Tooth had barely hit the water when several big splashes signaled the alligators were into him, grabbing the body from either side and shaking it with their sharp teeth.

“Damn! They smell the blood!” Gillom was breathing heavily, but didn’t have time to watch the frenzy, the big beasts dragging the body underwater to swim it down to their lair underneath the stone pile. He was already unbuckling the other teenager’s holster, picking up his revolver, too. The bandido groaned at the movement and his chest wound bled badly.

“Sorry, amigo, you asked for this. Can’t leave you … to recruit Serrano’s other kin. You ain’t gonna recover anyway.”

After rifling his pockets, he pulled the younger Mexican to his feet, hoisted him over his shoulder.

The vaquero groaned “Noooo” as he tried to grasp the pistols in Gillom’s holsters. Gillom staggered under the young man’s weight, but got himself turned round and lunged forward several steps to push the youth over the metal barrier to drop him on his butt inside the pond with another splash. The cold water woke the teenager from his lead-shocked daze. But his blood was already in the water.

Gillom hurriedly gathered his plunder outside the fence, the worn holsters and old, scratched pistols, the Mexican money and small buck knife. He saw several people moving outside the entrance to the hotel across the way, trying to ascertain the source of the gunshots in the night. A couple drunks weaved outside one of the saloons across from the park’s south end, but they were shouting and singing.

As Gillom picked up Gold Tooth’s gun belt and holster, with a schlooosh the biggest alligator, twelve feet long in the darkness at least, leapt out of the water and grabbed the sitting Mexican kid by the left shoulder in its mighty jaw. The crunch of collarbone through his coat was unmistakable.

“Aiiiyeeee!” The youth was yanked backward by the gator’s savage grip. The beast’s thrashing and heavy weight dragged its second victim into the pond and underwater into its death roll with only a muffled moan and a furious roiling of water.

“The gators got something!” one of the hotel guests yelled and started to run over. Gillom ran south along a plaza pathway, arms full of his antagonists’ weapons. He was horrified by the alligators’ blood thirst, had never seen anything like their attacks before, and felt no satisfaction in the killings. He was simply grateful to be alive, his guts still intact.

Gillom slung himself and his booty over the iron fence around the plaza, then yanked the Mexicans’ horses’ reins loose, drooped their holsters over the second one’s saddle horn. As he trotted his prizes away, a policeman’s whistle shrilled through the midnight air.

Ten

Bond Rogers was surprised to find her son already up and heating a coffeepot on her woodstove when she appeared in the kitchen early next morning.

“My, you’re serious about finding a job today.”

Gillom wore new Levis and dark brown cowboy boots; his long gray undershirt was rolled down to his waist as he pumped water into the kitchen sink to wash. Probably should shave, he thought, but no time for that now. He toweled off as she poured their coffees.

“Ma, I am going to find a good job, but not in El Paso. Have to leave today. For a while.”

“What? Why?”

“Well, I got into a … shoot-out … last night. Late. In San Jacinto Plaza. Shot a couple of young Mexicans, Serrano’s kin, who’ve been followin’ me.”

His mother paled. “My God. You’ve turned into a mankiller … just like Books.” Suddenly out of breath, she sat down hard.

“Ma, they trailed me on the street outside here, to church yesterday, then down near the river when I was practicin’.”

“Practicing? With those guns?”

“My gosh! I have to be able to defend myself!” He paced as he wormed back into his undershirt. “Those two vaqueros stalked me! Mister Books killed their uncle in the Constantinople. A rustler named Serrano, a real bandido. I delivered Books’s saloon invite to him, across the border. So his young relatives decided they had to kill me! It’s their blood honor or some crazy Mexican vendetta. It would have gone on and on, so I had to end it last night. Pronto.”

“My son. A shootist.” She was dazed, not quite comprehending his wild story or his reasoning.

“It was them or me. Younger one shot first.”

“You just left them wounded, lying there in the dark?”

“No. They were next to the alligator pond. I think their bodies have been disposed of. Nothing left to connect to me.” He wrung the towel in his hands, fretting. “But their relatives will come looking for them. And if they talk to Thibido, and he puts two and two together, he’ll come right to our front door. You know the marshal wants those fine revolvers, or me in jail.”

His mother stared at him, unhappy and dismayed.

“Why can’t you just give Marshal Thibido those guns? Buy him off this … this endless trouble.”

“No, I’ve got to vamoose. I have those Mexicans’ horses and pistols. I’ll sell ’em, out of town. Then take the train to Santa Fe. Always wanted to see that old trading post. I’ll find a job, bank or train guard, something honorable, where my gun skills are useful.” Gillom reached for her hand. “I’ll be fine. I’ll come back in a year or so, after these shootings are forgotten. Thibido may even be out of a job by then, and leave you and me and my guns alone.”

His mother started to cry, gulping air in and out as the f

inality of all this bloodshed washed over her. “How can … our stars … have gotten so crossed? What did we do … so awful … to deserve John Bernard Books … showing up at our front door? Cursing us!”

* * *

Gillom had the Mexicans’ horses saddled in an hour. He ground-reined them in his mom’s grassy backyard, away from the nearby street’s prying eyes. These horses were stolen and he was taking a risk, but he didn’t intend to keep them long.

His mother cooked him a hurried breakfast of oatmeal and bacon, then loaded her only child up with half the foodstuffs in her pantry in a canvas bag. She was filling his bulging warbag with a small frying pan, while he tightened one hemp cinch underneath the big saddle and hopped onto the black horse, the friskier of these caballos.

“Got your wool mittens?”

“I’ve got new leather gloves in my bags, Ma. Weather’s mild, won’t even need ’em.”

“Nights get cold in the desert. You’ll catch a chill.” She couldn’t look at him.

“I’ll be fine. Sell these horses and tack when I get into New Mexico, catch a train for Santa Fe.”

“Write me often. So I know where to reach you when it’s safe to come home.”

“I will, Ma. I promise.” He leaned down to buss her cheek. That set her tears flowing again. “I won’t rest in jail again, either.”

“Couldn’t bear to lose you, Gillom. Not after Ray. I’d grow old. Alone.”

“Year or two at the most, Ma. When this all blows over, I’ll come back.”

She clutched his arm. “Promise you’ll stop this pistol-fighting. Please! Don’t shoot anybody else!”

He jerked the black horse’s head sideways, turning the gelding out from behind the house toward their front yard, led the smaller bay filly along behind by its mecate reins. He’d buried his choice revolvers in his saddlebags until he got out of town or she’d be trying to grab those, too.

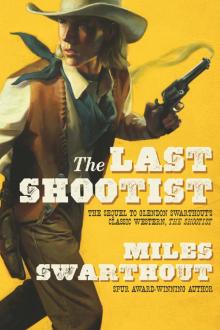

The Last Shootist

The Last Shootist