- Home

- Miles Swarthout

The Last Shootist Page 6

The Last Shootist Read online

Page 6

She was crying, semihysterical. “Gillom! Please! No more killings! It’s not right! It’s not our way!”

He didn’t favor his distraught mother with a wave, or even a look back.

* * *

Gillom surprised Mose Tarrant in his stable so early, feeding his paying guests. Mose asked where he’d found these two nags, if the kid had gotten a good deal? Gillom lied and resisted the horse wrangler’s entreaties to buy Books’s overpriced horse, Dollar, instead. But he did swap the worst of the Mexicans’ saddles for Books’s custom saddle and open reins, a snaffle bit with a high port and several ornate cheek pieces on a split-ear, leather headstall, plus one hundred and fifty dollars. Books’s saddle was a Myres double rig with a low wooden horn, bow fork, and a square leather skirt. Mose had found a brown leather breast collar that sort of matched, which he’d tied onto the front of the saddle to prevent slippage. Double cinches made the big saddle more secure, with less movement on the horse’s back during jarring movements like sudden stops. Gillom wanted something more comfortable to ride on, for he was going a long ways, and it was why he’d decided to trail two horses instead of one. Old Mose wet-thumbed his money, hiding it in his leather snap-top purse, pleased to get monetarily even with this snaky kid, as Gillom rode away. Neither bid the other farewell.

* * *

He avoided the downtown’s center around San Jacinto Plaza, the scene of last night’s hellish confrontation. God knows what body parts might have floated up today, he mused. But Gillom did stop at his favorite haunt, the Acme Saloon, Wes Hardin’s infamous headquarters. A bleary bartender didn’t blink at selling a pint of whiskey to a minor, since there were no Laws about that early to catch him doin’ it.

“Long as you don’t drink it in here, kid.”

Gillom was stuffing the bottle into a saddlebag when Dan Dobkins spotted him as he strolled out of a nearby breakfast parlor. Dobkins had on another loud, checked suit that didn’t match the yellow-and-black shoes he danced across the street in.

“Young Rogers!”

Gillom winced as the newspaper reporter sped over.

“A packhorse? Going somewheres distant?”

“Visiting some relatives. You made it too hot for me here, Dan, writing that stuff in the Herald.”

Dobkins cleaned what was left of breakfast from his teeth with a matchstick.

“Power of the press. Promised I’d make you famous.”

“Notorious is more like it. Now I can’t find a job here, can’t go back to Central School. And Thibido’s tryin’ to steal J. B.’s guns, even after Mister Books promised ’em to me.”

The newsman shook his head, feigning empathy. “Price of infamy, kid. You get collared as a killer, it’ll haunt you.”

“You done?” Gillom mounted up. “What did John Wesley Hardin say? ‘My enemies are many, but my sword of retribution is my six-shooter.’”

The newshound eyed him speculatively. “You’re a real cocked pistol, kid. You get over into New Mexico, stop in Tularosa, ask directions to Gene Rhodes’s ranch, west across the white sands up in the San Andes Mountains. Eugene’s a tough bird. He’s that aspiring fictionist I mentioned. He’s got a weakness for desperados ridin’ the Owl Hoot Trail, so it’s reported.”

Gillom had the black gelding moving, but he just nodded, leading the dark brown packhorse away.

Dan watched him go. “Owe you one! You come back to the Pass, Gillom, I’ll buy the drinks and you tell me your adventures!”

Gillom turned in his saddle to give Dobkins a hard smile, but he didn’t wave goodbye.

Eleven

Gillom rode north from El Paso aiming for Tularosa, the only destination that stuck in his head from Dobkins’s advice. He knew only that after last night’s nightmare with the alligators he had to get the hell on his horse, or these two stolen ones, and get gone for a long while.

He still had two hundred and fifty dollars of Books’s inheritance burning in his saddlebag, plus the young Mexicans’ old revolvers and holsters he’d trade for supplies along the way. I hope those crazy boys are still missing, he thought. It was street wisdom among El Paso’s youth that their park’s famous alligators hid their victims underwater in their rocky grotto to gnaw on later for snacks. Hope to God parts of those vaqueros, Serrano’s kin, don’t float up to give me away!

The black horse was feisty under its new rider, chewing its snaffle bit, shying sideways, but Mose had told him this bar bit with a hinge in the middle was easier on a horse’s mouth. Gillom gave the gelding a little iron of the new spurs he’d also picked up at the Fair store. He nearly lost the reins of the packhorse following as he clung onto the saddlehorn during the bucking that followed. Lucky Mose sold me that breast collar, he thought, so my damned saddle won’t fall off! Gillom aimed the big horse upslope on Mt. Franklin until its consternation subsided.

El Paso had grown up on both sides of this mile-high wedge of limestone and granite shaped like a horseshoe, and he rode along the rocky foothills of the western side of Mt. Franklin, which gradually sloped down to the big river to the south.

But Gillom was headed away from the Rio Grande, weaving through patches of lechugilla and yucca, enjoying a morning sun filtering through mountainside stands of live oak and juniper trees. He was confident enough to ask an old Mexican goatherder chopping down a piñon pine, “How far to Tularosa?”

“Tularosa? Tres dias,” the old man answered, scratching his chin hair.

“One hundred miles?”

The old Mexican understood English. “Mas o menos.”

I’ll tire these ornery animals ridin’ forty miles on each of ’em these first couple days and then just ease in that third day for a layover till I get my bearings, Gillom decided. Tularosa’s supposed to be a tough town. Excitin’!

He rode down the mountainside and out of the coffin corner of Texas.

* * *

It was dark when he reached a stream leading into Old Coe Lake, out in the lower middle of the long Tularosa Valley. The lake was too big to be anybody’s fenced-off waterhole, but too small to be good for fishing. Even if he knew how to fish, Gillom was too tired to try. His thighs and butt and lower back ached from a full day in the saddle, which this town boy wasn’t used to. He staggered as he pulled the sweaty Navajo double blanket and saddle off the bay horse he’d switched to riding midday, to give each mount a breather from the packed saddlebags and man they had to carry. Taking hardtack from the food sack in his warbag, Gillom led both tired horses down to the stream. While they guzzled noisily, he unbuckled his new twenty-five-dollar Bianchi spurs, yanked his boots and socks off, and splashed into the chilly flow alongside his stolen horseflesh. The spring freshet felt so good, he flung off his new felt hat and cotton shirt to sluice his sweaty chest in a whore’s bath.

Gillom managed to find in the dark the leather hobbles Mose Tarrant had thrown into his tack sale. One was unusual, a fore and hind leg “cross-hobble,” which he finally attached to the reluctant gelding’s hooves by the rising moonlight. Their reins removed, the two horses were left to browse as he untied his canvas-wrapped bedroll with wool blankets inside, rolled up in them and, still chewing a chunk of hardtack, fell into exhausted sleep with his head against J. B. Books’s own saddle.

* * *

He awoke to one of the horses nibbling grass near his ear. While stretching the stiffness out of his legs, Gillom gathered sticks for a small fire, filled his coffeepot and canteens in the stream. He stuck head and shoulders underwater and blew bubbles to wake fully up, then walked back to his fire shaking water from his wet hair like a dog. He’d decided to eat mostly on the move, holding off regular meals until Tularosa, where he could rest and figure out what to do next.

If this Rhodes fella ain’t there, I’ll ride west, over the mountains to Arizona, he decided. Prescott’s the territorial capital, so it should be a hoppin’ town. Or maybe ride down to Old Tucson in the Sonoran desert, before their summer heat hits. Tucson’s a famous old tradin’ p

ost I’d like to see.

After horse and rider loosened their leg muscles, Gillom booted the bay mare into a hard trot, wanting to put long miles on while the day was still cool. He aimed northeast, trying to hit the El Paso and North Eastern rail line, which had been completed across the Tularosa Basin only three years before in 1898.

A wide sky sprayed light blue with thin swatches of clouds, across which birds winged. The vast emptiness of the Tularosa Valley was so peaceful Gillom’s worries from the two weeks since John Bernard Books had ridden up to his mother’s front door took wing, too. He crunched one of Bond Rogers’s biscuits.

He kind of missed school, sorry that his run-in with the marshal and Books’s shocking suicide and his own temper had all conflagrated so quickly to make him a pariah even among his buddies, an undesirable at high school. Ahh, to hell with my senior year! Wish they could see me now. Free as a bird and rich to boot! Bee, Ivory, and Johnny would be jealous of my free-ridin’ life. Green with envy, especially Mr. Kneebone, Jr. The thought pleased him no end.

Lunch was hardtack washed down with water, while he lazed in the grass giving the horses a half hour blow and a hatful of corn. Then he switched tack again, putting Books’s saddle on the black gelding. The bigger horse didn’t fight the bit so much today, the unfamiliar saddle, so Gillom didn’t have to grip tight with his sore thighs, alert to the sudden buck or occasional sidestep by an anxious horse.

To relieve the boredom of his slow ride, Gillom practiced. That morning, concerned about highwaymen, he unpacked Books’s guns and strapped them on. He reversed the handles of the black and pearl revolvers so he’d be less likely to knock them out of their holsters if he suddenly had to do any hard riding. Gillom practiced his cross-handed draw with each hand a few times, then both at once. Spinning the nickel-plated beauties on his index fingers like Catherine wheels, forward, backward, halting quickly with a twist of his wrist to slip them reversed back into the leather holsters. Gosh! Did I leave the chamber under the hammer empty like Books warned me to do? He checked each cylinder. If I shoot myself or one of these horses in the leg accidentally, I’m in a damned pickle. Be careful, buddy.

But of course he couldn’t be for long. Careful. Boys with guns for toys just had to play with ’em, spinning them upward, downside on one crooked finger. Gillom wrapped the long reins of his follow horse around his saddlehorn, so he could take aim with each hand, squinting at fence posts, rabbits bursting from the brush as he passed. When that game paled, and since he didn’t want to call attention to himself by actually firing for marksmanship, he got fancy, pinwheeling a Remington up in the air, catching it by the handle again after a full rotation as the butt dropped naturally into his palm. Reversing the revolution, too, by tipping the five-and-a-half-inch barrel with his forefinger so that it tossed up butt first, and brought his left hand into play, so it was ready for work, false-fanning the hammer when he caught the big pistol again by its handle on its drop. He was quick, very quick. His reflexes, hand-to-eye coordination, distant vision, Gillom Rogers had it all, the lightning-fast instincts of a gifted athlete, or a gunfighter.

It was only when he pushed his tricks too far, flipping the .44 up from behind his back with a twist of his wrist and lowering his right shoulder, that he missed a catch. The heavy revolver bounced off the horse’s flank and then to the dirt, spooking the animal. Gillom had to grab the saddlehorn and unwrap the reins of the follow horse to get both startled animals calmed down after a few bucks and snorts. The gunslick dismounted and walked the skittish horses in a circle before retrieving his Remington from the dust. Better leave the gunplay for standing up, he realized.

His fingers were as sore as his legs when he made camp at a grove of cottonwoods early evening. The horses he watered at another small stream and since it was twilight he risked a fire. In the dimness smoke wouldn’t show much and it was still light enough for his tiny blaze to be invisible at a distance. Any Indians around, though, could smell the smoke with their keen noses. Apaches had raided regularly throughout southern New Mexico, but this was a new century, although he’d heard there were still some wild ones left down in the Sierra Madres. Gillom pondered noises in the night now drawing about him while he enjoyed his first full meal of beans and bacon in nearly two days. He licked the skillet clean before nodding off with a slice of moon for dessert.

He awoke to a chilly wind blowing across his blanket. Dust began to swirl. Gillom blinked. Damn! Another spring dust storm! When the spring temperature was in the seventies, conditions grew ripe for winds around El Paso to blow in from the west. These big dust storms, hundreds of miles across, could reach fifty miles an hour, gusting higher.

“Clean sand is healthy for your character,” his dad used to tell his tyke. “It polishes up the town.”

Gillom wasn’t as sure of the medicinal qualities of flying dirt as he choked down a dry biscuit while saddling. A last drink of water for the horses, a faceful for himself, and then wet handkerchiefs tied round his neck and pulled up over his nose, trying to filter out the grit. These sandstorms every spring stung like a slap across the face, reminding one the Southwest still wasn’t fully tamed.

They moved northeast to Gillom’s reckoning, riding slowly into blowing sand for what seemed like hours. Finally he raised his head, squinting against the scratchy dust, for they’d reached a rise in the hard-packed ground.

A railroad track! Coughing, he dismounted to take a piss. Relieved, he gulped water from a canteen and washed his dirty neckerchief to retie over his nose. It was too difficult in this strong wind to switch saddles, so Gillom moved his bedroll and warbag from the back of the Mexican’s saddle he hadn’t traded to Mose Tarrant and tied this gear onto the back of Books’s big saddle atop the gelding he’d been riding all day, turning it into his packhorse. Adjusting the narrow, leather-covered Oxbow stirrups, tightening the single cinch, he climbed atop the smaller mare and set out again into the storm, pulling his worn black horse along behind.

An old El Paso adage that the wind went down with the sun once again proved true. He saw lights beginning to twinkle in a town in the distance. But Gillom still looked like the sandman, so he reined his horse and dismounted. The teenager partially stripped, shaking like a dog, then stretched, trying to shed grains of sand which seemed to have embedded themselves in every crease and crevice of his pale skin. He rebuttoned with one hand while chugging the last of his canteen water with his other. Gillom switched horses again, too, back to riding the black gelding.

Gotta look good, he thought, hittin’ Tularosa.

Twelve

Tularosa had the black reputation of an outlaw town, where unsmiling men arrived by horse or stage, between two suns and one jump ahead of the sheriff. Laws there were minimal and their few enforcers indulgent. It was a community of small farms growing alfalfa mostly, worked by Mexicans with a liberal splash of gringo blood running the town’s businesses. Swift Tularosa Creek watered the long and narrow town with fingers and thumb of orchard and farmlet via acequias off the smoother ridges as they fell away from the narrow shelf of land below the Sacramento Mountains, which loomed barrier-long to the east. Transplanted Texans ran their cattle near springs in the stony hills and slopes extending up into the mountain range and fed their herds and horses on that alfalfa during the harder winters.

Gillom rode past mud-daubed adobes and a couple more substantial structures, the Santa Fe railroad office and the post office. It was a town of little shade. He smelled the stable at the south end of the town before he rode up to it. The old stableman was more interested in his supper, but they bargained a wash and a couple days’ feed for his two tired horses.

“Gene Rhodes? Yeah, I think he’s in town. Either at his wife’s house, or at the Wolf, playin’ cards. Right down this street, right-hand side.”

“Where can I get a good meal, maybe a bath, this time of night?”

“Tularosa House, center of town. Expensive, though, if they ain’t already full.” The proprietor sc

ratched his stubble. “The Wolf, too. Bed down in their storeroom, them that’s over-indulged.” The old man smiled, displaying partially vacant gums. From the odor off him, this wasn’t the man to ask the whereabouts of a bath.

The Wolf was better than he expected, with its head of the predator painted larger than life over the batwing front doors. A real grey wolf’s head was mounted over the bar inside, jaw stretched, yellow teeth frozen in a snarl. Intimidating, especially on a dark night with a few whiskeys in your gut.

Gillom limped to the long counter, feeling every muscle ache after three days in the saddle, by far the longest ride he’d ever taken. The tall bartender eyed his young, grimy guest skeptically.

“Mister, I need a bath and a bed for the night.”

The barkeep smoothed his waxed mustache. “Can throw your bedroll in our back storeroom for a dollar. Wash trough out in the alley is free. Towel’s your own.”

“I could also use a beefsteak, burnt, fried potatoes, and a beer.”

“That’s two dollars. In advance.”

Gillom dug into his grimy new jeans for two singles, which he thumbed from a wad.

The bartender took his money. “Drop your gear in back. Time you clean up, your supper’ll be ready.”

Gillom Rogers smiled for the first time in three days. Sauntering down the long bar, his limp forgotten, he noted the free lunch set out—pretzels, sausages, mustard, olives, crackers, and cheese. He helped himself to a pickle, crunching it, letting its sour juice run down his chin as he went out back to clean up.

* * *

Refreshed, Gillom sat at a table near the bar, demolishing his steak while he looked around the long barroom, lightly patronized this spring weeknight with a scattering of players at the monte, faro, senate, and poker tables, ending at an empty billiard table in the rear. In this outlaw town they had no trouble with a teenager drinking, so Gillom motioned for another brew. As he was served, he queried the nattily dressed bartender.

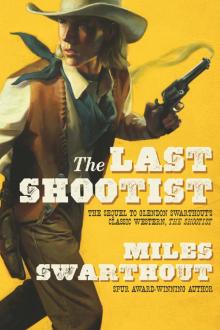

The Last Shootist

The Last Shootist