- Home

- Miles Swarthout

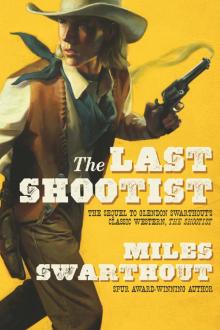

The Last Shootist Page 4

The Last Shootist Read online

Page 4

“Hooligan’s Troubles is playing down at the Myar Opera House, Gillom! Maybe you can get a starring role!”

Seven

His mother ordered him to stay home that afternoon, out of further trouble, while she visited several lady friends to spread word her son was seeking employment. Gillom watched her walk off in high-button shoes, stepping high, like her feet hurt with the task. The house was silent as he stood in the bedroom where J. B. Books had killed two midnight assassins only a week ago. Until echoes from that bloody set-to died down, Bond Rogers wouldn’t have to slave afternoons cooking more big meals for boarders. They were all gone.

Sure his mother was gone, Gillom left the house and headed for Mose Tarrant’s livery stable. All he needed now was a horse and tack. With that damned marshal chasing me and my pistols, he decided, I gotta get the hell out of El Paso for a while.

He hurried along Overland Street, keeping his head down under his new Stetson. Tarrant’s stable was on Oregon Street, a cross street. He walked south, toward the river and Mexico. Glancing back, Gillom saw two Mexicans riding slowly along the street after him. Gillom had noticed these two young men sitting beside the dirt road under a shade tree, holding their horses’ reins and conversing as he passed.

Gillom checked behind before entering the stable, and sure enough, the two Mexicans on horseback were still dogging him. Inside, Mose Tarrant was attempting to curry an anxious stallion tethered outside its stall.

“Mose! I need to buy a horse!”

“Whoa, settle down there.” Twisting the stamping stallion’s bridle, the liveryman turned the gray horse’s rear hooves away from his new customer.

“Got any money?”

“Yes, I do,” nodded Gillom. “Mister Books left me a little.”

“Really? After that shitty trick you pulled, sellin’ me Books’s horse without his permission?”

“Well, said I was sorry. Thought we settled our personal differences … before his shoot-out. You still got his horse?”

“Yessir. Dollar. His fistula’s healin’. Expensive animal, though.”

“How expensive?”

“Three hundred dollars.”

“What! That horse ain’t no racer.”

The older stable owner gave the teenager a mercenary look. “Son, that horse belonged to John Bernard Books.”

“Well, I just need a fit animal to ride. Doesn’t have to be blooded stock.”

“I’ll look around. When do you need this mighty steed?”

“Oh, next couple days. You still got Books’s saddle?”

“I do.” The tall, stooped white man gave the stallion’s mane a couple last swipes with his brush, then led the restless bangtail back into its stall.

“Hundred and fifty dollars for all his tack.”

Gillom shook his head. “Pretty dear.”

“Hey, that’s a Myres saddle, a good double rig. Where you ridin’ to?”

“Oh, north, probably. Into the mountains.”

Mose Tarrant ran long, dirty fingers through his own thinning hair, brushing loose straw from the tangle.

“Then you’ll need a breast collar, too, so that big saddle won’t slip back when you’re climbing. Might throw that in for the price.”

“See what I can afford.”

“Tomorra’s Sunday. Come back Monday, see if I’ve found anything can still trot.”

Gillom grinned. “Gallop would be preferred. Thank you, Mose.”

Mose Tarrant cleared his throat, expectorated into the pungent dirt on his stable’s floor. “Don’t forget to bring your money, Junior. All of it.”

Gillom stuck his head round the barn’s corner to peer both ways, up and down busy Oregon Street. He saw several Mexicans going about their business, but not those two young vaqueros.

* * *

Next morning, his arm hooked into his mother’s, Gillom attended church. Methodists occupied the greatest number of churches at this turn of El Paso’s century, five, and Gillom was seated in a pew of the oldest, Trinity Methodist South, on the corner of Texas and Stanton. His mother wanted his attendance noted but not to put Gillom on display, so they were seated near the middle of the congregation. Bond Rogers sat on the aisle, so her son couldn’t escape.

From his pulpit, the Reverend Henry New was excoriating his flock about sinners swimming in “hot agua,” and how he’d rather be a doorkeeper in the House of God than dwell outside forever in the tents of wickedness. Biblical hot air drifted over Gillom like sleep until a rap in the ribs from his mother startled him awake. The preacher was climaxing about the Lord leading him to a sacred rock that was higher than he was, when the youth’s bored glance out one of the side windows caught sight of two Mexicans riding slowly up to one of the tall oaks in their church’s backyard. The young vaqueros halted and bent to speak to one of the girls skipping rope outside now that Sunday school had released. Gillom sat straight up in his pew seat. The little girls gabbed with those same Mexicans and pointed toward this church!

Gillom was restless through the final hymn and benediction, while the riders sitting their horses under the big oak were patient, quiet. After the service, Gillom tried to bound down the front steps past Henry New, but the reverend was too quick.

“Gillom! Any luck with the job hunting?”

“No, sir. But I plan on goin’ lookin’ tomorrow.”

His mother wedged in her two cents. “I heard Jay Cobb’s parents need somebody to deliver milk from their creamery, after what happened to their poor son in the Books tragedy.”

Reverend New’s smile folded into a funereal frown. “Their only son. Those who live by the sword, or the six-gun in young Jay’s case, shall perish by it. I must step round with my condolences.” He turned back to Bond’s wayward son. “Milk deliveries would be a starter job, Gillom, until you found something better. Did you find those pistols?”

Gillom wasn’t partial to a Sunday grilling, especially with other parishioners hovering.

“Nope.” Gillom pushed from the knot of people awaiting the preacher’s blessing and down the front steps. The reverend, however, always liked the last word.

“Hope you’re not back in jail before you find a job!” he yelled at the retreating young man.

Bond Rogers stood embarrassed. Realizing even he might have overstepped the bounds of propriety, the parson patted Mrs. Rogers’s wrist.

“A wise son maketh a good father, but a foolish son is the heaviness of his mother.”

Mrs. Rogers gave her preacher a hard eye before marching away from the gossiping churchgoers.

There was no stopping Gillom as he strode toward the big oak up the grassy rise. Seeing him coming fast, the two Mexicans were already turning their horses.

“Hey, you fellers! Wait up!” The vaqueros gave their mounts the spurs. Only their dust lingered.

* * *

That afternoon Gillom told his mother he was going to see his pals.

“I can’t look for work, it’s Sunday. Maybe Bee or Ivory will know of a job, or they can spread the word at school tomorrow. See if anyone’s dad’s looking for someone full-time.”

“I’m surprised those boys would have anything to do with you after you shot at them.”

“That was just at Kneebone, after he stuck his knife in my bare foot. Don’t believe everything the marshal said, Ma. I’m still friends with most of the kids at school. They ain’t scared a me.”

Mrs. Rogers rubbed worry from her hands. “I certainly hope not. You’ll never find any job if people are afraid of you, or hear even a whisper you’re dangerous.”

“I’ll be back for supper.”

“Think you’ll find those pistols?”

Gillom’s grin turned downward. “Don’t bet on it.”

“Don’t make J. B. Books your dime novel hero, Gillom. He was nothing more than a shootist.”

“Maybe, but he also made history.” Then he was out the front door, bounding down their whitewashed steps. He gave his mother a backhande

d goodbye as he strode out their front gate. He halted on their wooden sidewalk to check up and down Overland Street, looking for Mexicans.

No spies in sight, so he turned left, away from downtown. When he saw his mother had closed the front door of their two-story brick house, he side-straddled their back fence, ran to the woodpile behind their backyard tool shed. Moving some firewood, Gillom dug out Books’s revolvers again from their burlap swaddling. He’d soaped and cleaned the leather late last night in his bedroom closet, then oiled the old holster to preserve it and speed his draw.

I’ve gotta practice, he realized. Fire these pistols before somebody tests me. These two Remingtons are gonna be my only protection from thieves and pistoleros trying to prove their speed, so I better get comfortable with ’em. These guns and I need to become friends.

Eight

The bundle tucked under his wool coat, Gillom hopped the fence again and walked west, headed past the growing city’s fringe. He knew of denser thickets, north of the Rio Grande, that were crossing points south for smugglers of guns, ammunition, cattle, and horses, with outlaws and tequila returning north through the same overgrown area. That dark country should be safe enough in the daytime, though, if he stayed on his guard.

Three miles outside El Paso, Gillom turned off the rutted road to hike into a bosque, a thicket of cottonwoods and heavy scrub brush just north of the river. Gillom recalled a big flood four years earlier in 1897 that had caused the Rio Grande to change course, isolating pieces of land between the old and new riverbanks. Gillom walked over the dry watercourse onto one such island, no longer legally in either America or Mexico until diplomats crossed sharp pens over the dispute. Brush-breaking was tiring, so he stopped to belt on his holster to free his hands. Ahead was a small clearing with a well-used firepit in the middle. He was entering bandit country!

Gillom sat down on a rock next to the fire ring to catch his breath and remove his coat. He picked up a small canteen he’d carried along, took water. He rolled up his shirtsleeves and took off his stiff new Stetson to enjoy some afternoon sun. Rising, he adjusted the single loop holster on his hips, making sure the double rig was belted low enough so his arms and big hands rested just below the revolvers’ trigger guards visible in their leather pockets for a fast pull. He loosened the leather tie-downs over the hammers to keep the guns snug in their leather sheaths. Then, first with his strong hand, he drew the pearl-handled .44 Remington smoothly but slowly, extended his right arm, closed his nondominant left eye, thumbed the hammer back, and fired. Gillom Rogers hit the tall tree he was aiming at, but not the target joint of its low-hanging branch.

He took a deep breath. Speed and accuracy need to be better, he realized. Adjusting his gunman’s stance a little wider, he reholstered his right revolver, stuck his empty right hand out for balance. He quick-pulled the gun on his left side with his off hand, extended his forearm, closed his dominant right eye, thumbed the single-action again, and pulled the trigger. This time his aim was wide, clipping a branch. His second shot was muffled by the dense underbrush. Wonder if my gunfire will attract any attention?

Now that the hammers of both pistols rested upon empty chambers, the safe way to practice in case he dropped a gun, he could practice firing without worrying about shooting himself in the foot. So practice Gillom did—fast draws, right hand, left hand, both hands, twirling the nickel-plated revolvers on his index fingers within their steel trigger guards, one revolution, two spins round, backward, forward, to make his reholstering look fancy. Again and again—quick pull, trying to make his hammer cock and the aim off his hips merely a reflex of hand and eye, without squinting, flinching, without even breathing.

Dropped the pistol! Damn! Be careful! Wiping sweaty palms on his Levis, he sucked breath and tried again. Right, left, both, again, until he had his fast draw fairly smooth with either hand.

Gillom stopped for a gulp of water. Since his first shots hadn’t drawn any unwelcome attention, he tried a trick he’d only heard about, never seen attempted. Pulling both revolvers suddenly, he cocked and fired his right Remington, then spun its pearl handle backward and flipped it into the air. While the first revolver somersaulted in the air, he quick transferred the black-handled grip from his weak left hand to his strong right, while attempting to catch the first pistol in his left palm as the gun spun round in the air. And missed!

He brushed dirt off its silver nickel plating, reholstered, and tried once more. This time he flipped the pearl-handled revolver higher, giving himself more time for the catch after the transfer, and achieved it. To celebrate he cocked and fired the black-handled pistol without carefully sighting and was rewarded by splinters flying from the cottonwood’s girth, seventy-five feet away. The border shift was tricky but essential to learn, for it allowed a gunfighter with an empty pistol to exchange it for a loaded weapon rapidly while under fire.

He dropped a pistol again, then made another successful transfer. Gillom began to complicate his draws, rotating each revolver once right out of the holster pocket as he spun them on each index finger and extended his right and left forearms, earring hammers back and firing at the end of each reach. Another drop. A blister formed on his right finger.

“Damn this is hard!” Gillom said aloud. Over and over, Gillom’s quick reflexes and sharp vision helped him whang chunks out of the distant tree almost every time. Maybe I’ve got the goddamned gift of gunfighting, he thought. What did that journalist call it—a bullet’s blessing?

He was reloading from a box of cartridges in his coat pocket when a bush snapped. While jamming cartridges in the revolver’s chambers, Gillom saw the crown of a wide hat above the breaking brush, a man on horseback. Now brush was crackling behind him, too! Spinning, he kept his left hand on his gun butt, his right revolver cocked and pointed at a black sombrero moving toward him.

Damn! That looks like one of those … Mexicans … been followin’ me! How in the bejesus did they find me out here?

The vaqueros had him sandwiched as they halted their scrawny horses in the brush either side of the clearing’s edge. Each wore a pistol on his hip, but both young men kept their hands on their reins as they sat cheap-looking saddles.

“You boys been followin’ me!”

The Mexicans held their tongues. His next question was a little more plaintive.

“Whatdya want?”

“Señor Gillom?”

“Yeah?”

The taller guy, who looked tougher, more aggressive than his younger partner, smiled. Maybe it was his black sombrero that intimidated.

“Ahhh, Señor Gillom. Did you invite Señor Serrano to his shooting?”

Gillom Rogers hesitated. “I guess.”

“An’ Señor Books kill him?”

Gillom slowly nodded.

Black sombrero waggled a finger. “Sí. It was you. Senor Serrano is his tio.” He pointed at the younger Mexican across the clearing. A flash of a gold tooth in a mouthful of pearlies. “Married to his sees-ter.”

“His uncle?”

“Sí. Tio. Un-cle. Now he must kill you. Caballerismo. Hon-or his familia.”

“What?”

The older young man nodded. “Sí. You help thees assassin, Señor Books.”

Gillom was astounded by this primitive logic. “No! I was just Mister Books’s messenger.”

“But you invite his un-cle to his murder. Mess-age of muerte, death. An’ then you shoot Señor Books, no? Journalista say. So Cesar must kill you. Justica. Por his familia.”

Their logic might have been crazy, but they didn’t appear to be fooling. Gillom pulled his second pistol and cocked it, training his left hand on the younger hombre to the south. The older vaquero grinned. “You prac-tice, pendejo. But no more bul-lets!”

They’re testing me, Gillom figured. Gotta show ’em.

Crouching to provide a smaller target even though he was standing all by his lonesome in the middle of a bare clearing, Gillom extended his right arm and squeezed the trigger of Books’s

big revolver. The .44-.40 slug clipped a branch of brush next to the mean Mexican, causing his horse to snort and shy sideways.

“Hokay, pendejo! Mi mis-take!” The twenty or so year old got his frightened horse under control, while his cousin across the clearing ducked, put his hands on his pistol’s butt, readying to draw. “No shoot you today, gavacho, but watch out! Serranos owe you!”

Touching a finger to his forehead goodbye, the black-hatted tracker began backing his skittish animal out of the thicket. His younger relative on the other side of the clearing began retreating, too. Gillom noted how underfed and unkempt their horses appeared.

My God! I can’t have these backshooters following me around El Paso, trying to kill me any goddamned time they please! That dark thought propelled him into an equally scary plan.

“You boys want a fair fight, meet me tonight!”

The older vaquero turned in his saddle. “Where?”

Gillom had to think a moment. “The bandstand in San Jacinto Plaza. Midnight!”

The Mexican pondered. “Hokay!” His gold front tooth flashed like a character flaw. “Mucha suerte, gringo!” He clucked to his horse and after fearsome moments of brush cracking, the vengeful young men were gone.

Gillom Rogers uncocked his Remingtons and reholstered. Bending, he put both hands on his knees, took another long, deep breath, and exhaled slowly. Godalmighty. What have I done now?

Nine

“How about working as a bellhop at the Grand Central? Finest hotel in all the southwest, three whole stories, and you’d meet important guests. Maybe lead to something better if you were polite and gave good service. Plus the gratuities, my goodness.” Gillom’s mother had a long index finger to her temple, helping her think.

“I’m not toting anybody’s bags, Ma, just cause they’re rich.”

“Well.… I read about the four C’s of growth in our region—copper, cattle, citrus, and climate. They never mention the fifth C, consumption. El Paso is paradise for the pulmonary invalid. We’ve got more consumptives and asthmatics in our sanatoriums than anyone can count, with more coming out every day to where sunshine spends the winter. They need strong, young aides to move those patients around. That could be a good starting job for you, health care.”

The Last Shootist

The Last Shootist